Cryogenic freezing or cryopreservation is the use of extreme low temperatures and specialized chemicals and techniques to preserve tissues and “cryonics” specifically refers to using those techniques to preserve a human body or brain. The goal of cryonics is to allow for future revivification using medical technology that isn’t currently available. Two organizations to know in the cryonics industry include Alcor and the Cryonics Institute, which currently have several hundred cryogenically preserved patients between the two of them, with thousands more signed up for the process.

Cryonic preservation can currently only happen for patients that are legally dead, but as Alcor points out there is actually a significant difference between this legal definition and true and complete biological death. Cryogenic freezing aims to preserve a body’s tissues in a state where they are still capable of the functions of life, trusting that medical science in the future will be able to restore biological life and consciousness.

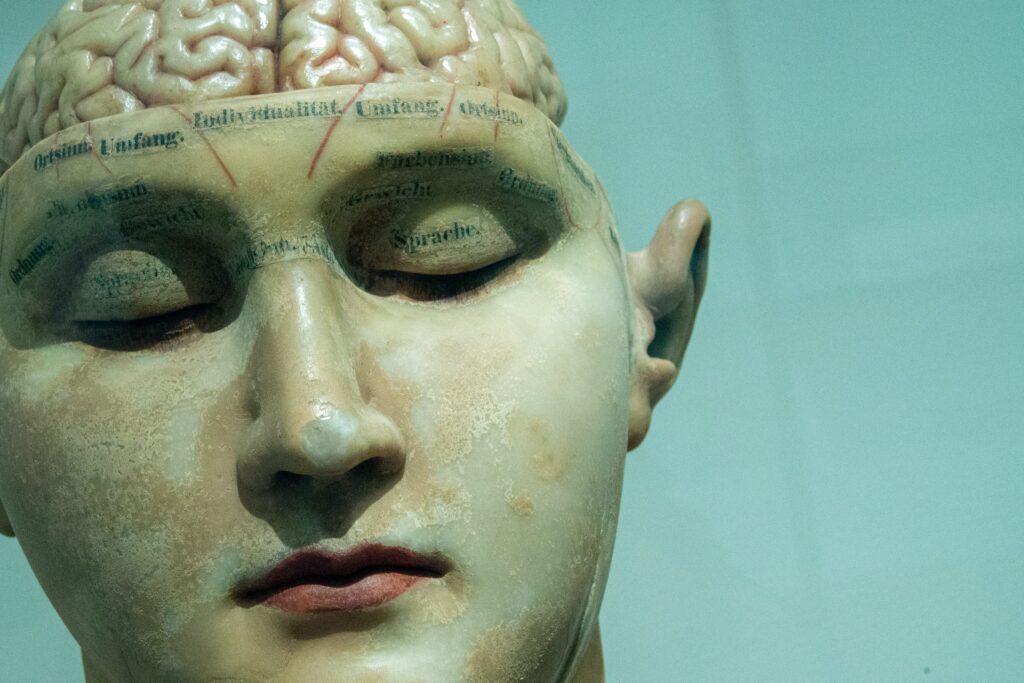

Though cryonics advocates generally share the same goals and beliefs about the process, there is one fundamental area of debate that splits the community and that has to do with how much of a person’s physical body needs to be preserved. Those in favor of neuropreservation think that the brain is the only critical physical structure that needs to be maintained hence.arguing that preserving a head alone is sufficient. However in many ways it is superior. Opponents who advocate for whole-body preservation instead believe that there are important reasons to maintain a person’s full biological body, despite the increased logistical challenges that come along with that.

Arguments for Neuropreservation

Improved Reliability

Cryogenic freezing is a complicated process and it’s easy to understand how focusing on just the head and brain during the actual freezing would make things simpler and cut down on potential issues. As discussed in the essay The Neuropreservation Option written by Steve Bridge, the former president of the Alcor Foundation, “a tight focus on the brain today results in shorter perfusion times; and once the freezing process begins, the smaller package of the head can be more rapidly cooled to temperatures where the biological and chemical activity are halted.” Choosing to preserve only a head allows the preservation to be done more rapidly and efficiently, which can only be a good thing in terms of preservation quality and the ease of future revivification.

But the improved reliability of the neuropreservation option doesn’t stop once the patient is frozen. As detailed in the article The Case for Neuropreservation, “a neuro patient requires one tenth the liquid nitrogen, and one tenth the storage space, of a whole body patient” which, according to author Brian Wilson, means that “Neuropreservation offers a tenfold increase in preservation security without apparent compromise of revival chances.”

To understand this, consider the logistics of keeping bodies vs. brains preserved over long periods of time, whether that be decades or centuries. The tissues are precious, and must be maintained at specific temperatures and under consistent conditions with minimal variation or interruption. But as everyone knows, no technology is perfect. From home computers to space shuttles, on a long enough timeframe bugs and breakdowns do occur. Organizations like Alcor and the Cryonics Institute have safeguards in place to prevent – or at least minimize – the problems that come along, but it’s clear to see that it’s much easier to successfully preserve a brain alone through unexpected occurrences, rather than a much larger full body. And freezing a full body requires the use of more cryoprotectant chemicals than just a head, which brings along its own questions of possible tissue damage and more complicated revivification.

Lower Cost

The cost of cryonics is another important factor for patients to consider. It’s not a cheap process no matter what form is chosen and it represents an additional cost that many people haven’t budgeted for in their lives – an expense that extends beyond retirement an uncertain number of years into the future.

Most patients pay for the cost of cryogenic freezing via an insurance policy and the difference in policy value required between neuropreservation and full-body preservation can be striking. According to Alcor’s FAQ page, whole-body preservation requires “a minimum policy of $200,000” while neuropreservation starts at just $80,000. That cost difference is going to translate into different premium payments during a patient’s life and many just won’t be able to get a higher value policy at all. For those patients, the neuropreservation option makes cryogenic freezing more accessible.

There’s another important way to think about cryogenic cost which Brian Wilson summarizes well: “Even if a person can afford whole body preservation, the same funding level will carry them much further as a neuro patient.” Cryonics is all about carrying a patient’s preserved vital tissues far enough in the future for advanced medical science to be able to revive them. Maintaining preservation for 200 years is going to cost more than maintaining it for only 50. But since we can’t currently know when science will progress far enough to begin reviving cryonics patients, it can be logical for a patient to choose an option that will get their all-important brain the furthest number of years into the future per dollar as possible. That makes a very strong case for neuropreservation.

While on the subject of cryonics cost, however, it’s important to note that Alcor’s numbers aren’t universal. The Cryonics Institute takes a much more pro-whole-body perspective than Alcor, and points out in their FAQs that their version of whole-body cryopreservation “costs as little as $28,000.00, rendering an alternative ‘neuro’ option unnecessary.”

Arguments for Whole-Body Preservation

Preserving the Brain-body Aspects of Identity

The primary argument in favor of whole-body cryopreservation is the simple fact that science actually doesn’t know for sure how much of an individual’s personality and identity are determined by factors outside of the physical brain itself.

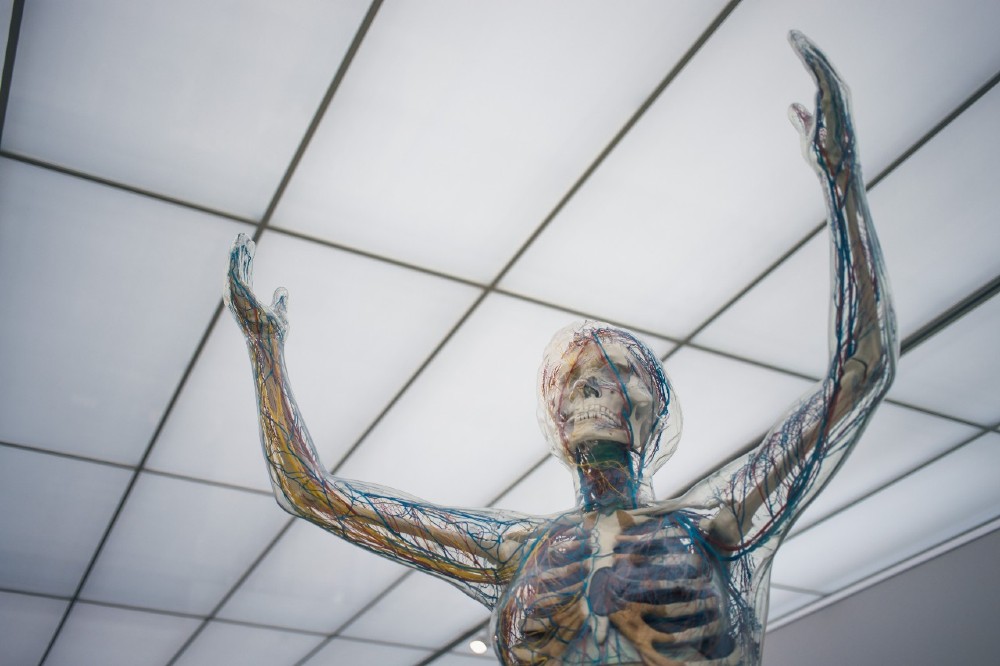

This topic is worthy of an article all its own, but to summarize briefly: human brains are not self-contained computers completely independent of the rest of the body. Factors like individual hormone levels and even gut bacteria are known to influence facets of personality like aggression, sociability, and anxiety. Most patients agree that the goal of cryogenic freezing is to preserve an individual’s identity after they are revived and from that perspective it’s valuable to preserve every possible factor throughout the body that has a role to play in that identity – and that extends beyond just the brain.

Neuropreservation advocates respond to this argument in a number of different ways. It’s of course true that biological changes happen over time in the normal course of human life. As hormone levels and gut bacteria fluctuate most people don’t consider that a person’s “identity” has been lost or fundamentally altered. Additionally, since many of the main arguments in favor of neuropreservation have to do with that alternative’s greater reliability over the long term, critics of whole-body preservation can contend that there’s no sense in using a less practical method in an effort to cling to small peripheral influences on identity. If funding or power consumption issues prevent a patient from ever being revived in the future, having their whole original body is of little consequence.

This question will likely remain an unanswered and contentious one until we reach a point where revivification is actually possible and we can compare the results of whole body vs. neuropreservation patients. Until data shows the contrary, whole-body advocates can contend that preserving the brain AND body is critical to preserving what we think of as an individual.

Less Uncertainty about a New Body

The neuropreservation argument holds that bodies are largely irrelevant when considered from the cryonics perspective. That’s the point of view shared by Dr. Max More, the Ambassador and President Emeritus of the Alcor Life Extension Foundation in Arizona, who personally plans to take the neuropreservation route. More says that he views his body as “replaceable” on cryonics timescales. Like many neuropreservation fans he assumes that future medical technology will be able to create a new functional body for him either through cloning or the use of artificial materials.

But going into the future as just a head means there will be additional medical procedures required in order to restore a patient to full and functional life, whether that be the creation of a newly cloned body to house the brain or the integration of the brain’s nerves with some kind of artificial body. Sure we can assume that these will be problems that future medical science can solve, once we’ve reached the point at which revivification from cryopreservation is possible, but each assumption we add to the cryonics equation leaves more room for something to go wrong or for funding to run out.

It could be possible within 50 years to revive a cryonically preserved patient and restore youth to their bodies via emerging longevity treatments, but what if a full brain transplant into a cloned body remains medically impossible at that point? If that’s the case then whole-body patients might be able to begin waking up and resuming their lives while neuropreservation patients remain frozen and waiting.

The Big Questions of Cryonics

Ultimately, cryonics is a practice with some fundamental unanswered questions at its core. Because it relies on assumptions about future medical technology that doesn’t currently exist, no one can know for sure whether neuropreservation or whole-body preservation will eventually prove to be the better option. Perhaps successful revivification in the future will discard old bodies anyway and whole-body preservation will have been nothing but unnecessary cost and complication. But it’s also possible that the medical science of tomorrow will rely even more on the full biological systems of the bodies in shaping identity than we can currently understand.

Metaphorically, cryonics is like planting a seed that you can’t identify. You can’t be certain what conditions are needed to help it eventually sprout and grow. But planning for cryogenic cryopreservation is also a very personal choice. Patients should consider the arguments on both sides of the neuropreservation vs. whole-body debate, and decide which form of cryopreservation is more appealing to them on an individual level.