When we think of the posthuman concept, we imagine highly advanced technologies, hybrid human-machine bodies with robotic prosthetics and sensory chips on the edge of science fiction; we imagine bodies destined for immortality thanks to the innovations in medicine and biotechnology, through cryogenic capsules or digital cloning. The boundaries of corporeality are challenged every day by philosophers, scientists, and enthusiasts, intrigued by the latest discoveries in science and information technology. Sometimes posthuman transformations are regarded as enhancements and greeted with enthusiasm, at other times they are perceived in dystopian terms, arousing reactions of fear or resistance. But, to what extent are these interventions on the human body justified? What is the boundary between improvement and distortion?

One common argument used to support the value of human enhancement is that the enhancement of the body by artificial devices would make it more efficient (or even immortal!). Scholars such as Katherine Hayles, one of the first theorists to use the term ‘posthuman’, were already highlighting the liberating power of the posthuman concept in the late 1990s. According to her most popular essay, How We Became Posthuman, posthuman identities would free themselves from the constricting dichotomy of mind and body, configuring themselves as fluid entities, half physical and half computerized, technological, virtual, and therefore improved and free.

However, the limits to human enhancement and the ethical issues surrounding the intervention on the human body are still the topic of debate in 2022. From euthanasia to plastic surgery, computer chip implants, gene-splicing or cryonics, modifications to the body, to its aesthetics and durability, all of these divide common opinion. They affect not only the sphere of science but also that of society and ethics, requiring people to make a collective rethinking effort. What would human beings look like in the posthuman era, in which they are no longer at their core like Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man but have established a new idea of their own passable and impassable limits?

Contemporary art is at the forefront of reformulating the concept of the posthuman body. It represents a compass in this philosophical and scientific challenge since it can embody the cultural climate of our time in advance of other disciplines. Artists – who are not the antithesis of scientists – have introjected the criticalities and revolutions of the posthuman, giving them material form. In this article, we introduce three 20th century artists whose art practices have explored this more-than-human dimension.

Neil Harbisson: the first cyborg artist

Neil Harbisson (b.1984) is an artist from Catalonia (Spain), musician, trans-species activist, as well as a cyborg. With a very recognizable appearance, he altered his body by implanting an antenna in his skull, which he calls an ‘eyeborg’. This antenna has helped him deal with a rare form of color blindness, called achromatopsia. This congenital condition does not allow him to see reality in color, but only in grayscale. With this bio-hack, Harbisson is instead able to perceive the variety of colors by turning them into sounds. The antenna is connected to a chip that converts the spectrum of light radiation into sound frequencies and musical notes, granting him a synesthetic experience of reality. Having acquired this special ability, Harbisson deals with artistic performances in which he turns colors into voice plays or concerts. Thus, it can be said that Harbisson’s operation is not just body-hacking but a revolutionary perceptive transformation.

Source: Wikimedia

The implanted artifactual sense grants cyborgs a different kind of perceptual and emotional experience of reality. Harbisson does not use technology; he is technology. His antenna is not an external device, but part of his body: physically, mentally, and sensory.

ORLAN's Body Experimentations

ORLAN (b.1947), is a French performer who, like Harbisson, directly investigates the transformation of her own body, but through different tools. She breaks the dogma of the body as something immutable, predetermined by nature, and therefore inviolable and unchangeable. Instead, she uses science and technology to show its fluidity and its possibilities for change. She is renowned for her performances in the 1990s, in which she underwent numerous plastic surgery sessions, documented photographically or even broadcasted live. It was indeed a campaign of self-transformation and facial refiguration, as she underwent nine facial plastic surgeries, some of which are bizarre, such as forehead implants, or facial alterations inspired by the canons of beauty in art history, such as the chin of Botticelli’s Venus, criticizing society’s standards of beauty!

Source: Wikimedia

Therefore, the use of cosmetic surgery in ORLAN’s practice is never functional or pushed by practical purposes, it is a statement of freedom and decision-making power, even going against nature. Her surgical performances, as Myers states, are difficult to watch as they are creepy and shocking, “but therein lies the power of this rethinking of the body”; they question the body’s standards of beauty and perfection, its limitations, and reinvent new, absurd, bodies.

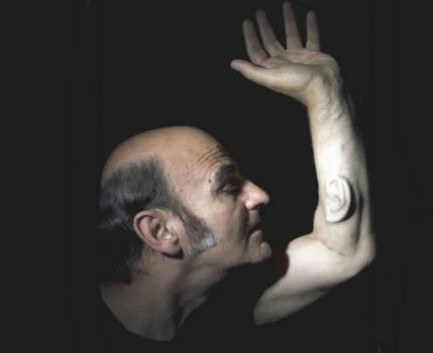

Stelarc and his extreme bio-art

The artistic practice of Cypriot-Australian performer Stelarc (b. 1946) is extreme. For the artist, the human body is, essentially, an obsolete device; the human species rather than being perpetuated through reproduction should enhance and redesign itself. But how? By integrating it with new technologies and robotics that can enhance its capabilities. Stelarc started with his own biological body, modifying it with invasive surgeries. Among his most famous endeavours, we find the “Ear on Arm” project. This involved the implantation of a third functioning ear on his arm. It took Stelarc more than a decade to find the right surgeon to carry out this extreme modification, a surgeon who would agree to his surreal proposal of installing this biocompatible prosthesis.

Source: Labiotech

The first operation was thus performed in 2006. Stelarc planned to undergo a final surgery that would transform the ear-in-progress into a functional organ, connecting it to the Internet. In this way, his third ear would be able to hear what is going on on the other side of the world. Similarly, Stelarc also put on performances in which he wired himself to the Internet, installing electrodes in his muscles that could be activated by even distant users. His bio-art blurs the boundaries between human and robotic, analog and digital, transforming the artist himself into a post-human being.

Conclusions

These three artists thus use biotechnology and prosthetics to create posthuman forms of life. However, as early as 1992, the curator and gallerist Jeffrey Deitch with his seminal exhibition Posthuman depicted the complexity of the issue: do these bodily expansions allow us to truly expand our identity by transcending the limits of the body and our genetic history, or, on the contrary, do they risk making us all alike and conforming? Do infinite choice and extreme openness lead to absolute identity freedom, or could they create a posthuman species of robots that are all the same? The first step we need to take is to become informed, curious, and discuss, to build a new code of ethics that distinguishes between positive and negative options for our increasingly mutable species.