The quest to find the elixir of life and conquer death has animated thinkers and philosophers for several millennia. Recent advances in life-extension and other technologies have made the idea of immortality more plausible—though not less strange.

Historically, escaping the inevitability of death remained an elusive pursuit, but that did not stop people from imagining what life without death might look like.

There are fascinating characters in myths, mythologies and works of fiction over the centuries who achieved immortality, though it didn’t necessarily end well for them. It’s as if storytellers and mythmakers throughout the ages were warning us about the pitfalls of immortality.

Let’s look at some of the fictional and archetypal characters who have tried to live forever.

The Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh (2150-1400 BCE), pre-dating Homer by some 1,500 years, is arguably the oldest poetic work dealing explicitly with the theme of immortality. Deeply affected by the death of his dear friend, Enkidu, king Gilgamesh leaves his kingdom in search for eternal life. In this remarkable Sumerian tale, Gilgamesh eventually fails to become immortal but the quest itself gives meaning to his life. Interestingly, the character of Gilgamesh is based on a historical figure who ruled in the 26th century BCE. Gilgamesh may not have become immortal, but the epic lives on. Most modern-day humans can empathize with his desire to live forever.

The legend of Tithonus

In Greek mythology, the story of Tithonus, the handsome prince of Troy, can be seen as a warning from antiquity about the unintended consequences of longevity. Tithonus falls in love with Eos, the goddess of dawn. But when Eos realizes that Tithonus is a mere mortal and will die one day, she begs Zeus, the god of thunder and lightning, to grant her lover immortality. But Zeus is a jealous god and mischievously grants Eos’s wish. He makes Tithonus immortal but does not grant him eternal youth. As a result, Tithonus grows older and older, and more infirm and decrepit. He even loses his mental faculties and babbles constantly. Eos can’t bear it any longer and turns him into a grasshopper, who chirrups ceaselessly. One of the challenges for life-extension technologies is exactly this: If people were to live longer, would they also live healthier and productive lives?

The Wandering Jew

Different versions of the story of the Wandering Jew have been circulating for a long time, but it was first printed in the 17th century. It tells us about the unenviable fate of a man who cursed Christ and as a result was condemned to wander till the second coming of Jesus. In one re-telling, the Jew is a shoemaker, and Jesus tells him, “I shall at last rest, but thou shalt go on till the last day.”

In all of these stories, the idea of living forever is seen as a burden—if not linked to Jesus Christ and Biblical teachings—instead of something to look forward to. On the other hand, for true believers, eternal life was a much more palatable concept—and this idea resonates strongly with many practicing Chistians even today. “This is eternal life, that they may know You, the only true God, and Jesus Christ whom You have sent.” (John 17:3) Since life-extension technologies have little in common with the Biblical world, it will be interesting to see how Christians respond to this.

The Struldbruggs of Gulliver’s Travels

In his 1726 masterpiece Gulliver’s Travels, Jonathan Swift wrote about the Struldbruggs, a people who never die but suffer the ravages of old age. In that sense, it is similar to the fate suffered by Tithonus. The Struldbruggs lose their teeth, hair, memory—and even the ability to speak with others. Finally, they become unhinged and monstrous. Scholars who have studied the legendary work believe that the Struldbruggs are depicted as being very close to achieving the ideal of the 18th century post-Reformation man, dedicating endless years to the pursuit of knowledge and science. But yet, the fact that they fall so spectacularly short of that ideal, by turning into loathsome figures, makes Gulliver realize that immortality is perhaps not something worth seeking.

The Mortal Immortal

Mary Shelley’s 1833 short story The Mortal Immortal is about Winzy, a man who drinks an elixir and gains eternal life. Initially he is happy but the length of his life begins to take its toll on him, especially after he realizes that his beloved Bertha will die. After her death, he feels he will never love another woman like he loved her. Besides the obvious criticism of immortality, the story also raises philosophical questions about the meaning of relationships for someone who is bestowed with eternal life. Does our knowledge of mortality make our specific human relationships more precious and, therefore, our lives worth living? The Mortal Immortal may not be as important in the literary canon as Shelley’s Frankenstein, but it reinforces the capacity to grapple with issues that are as relevant today as they were in the first half of the 19th century.

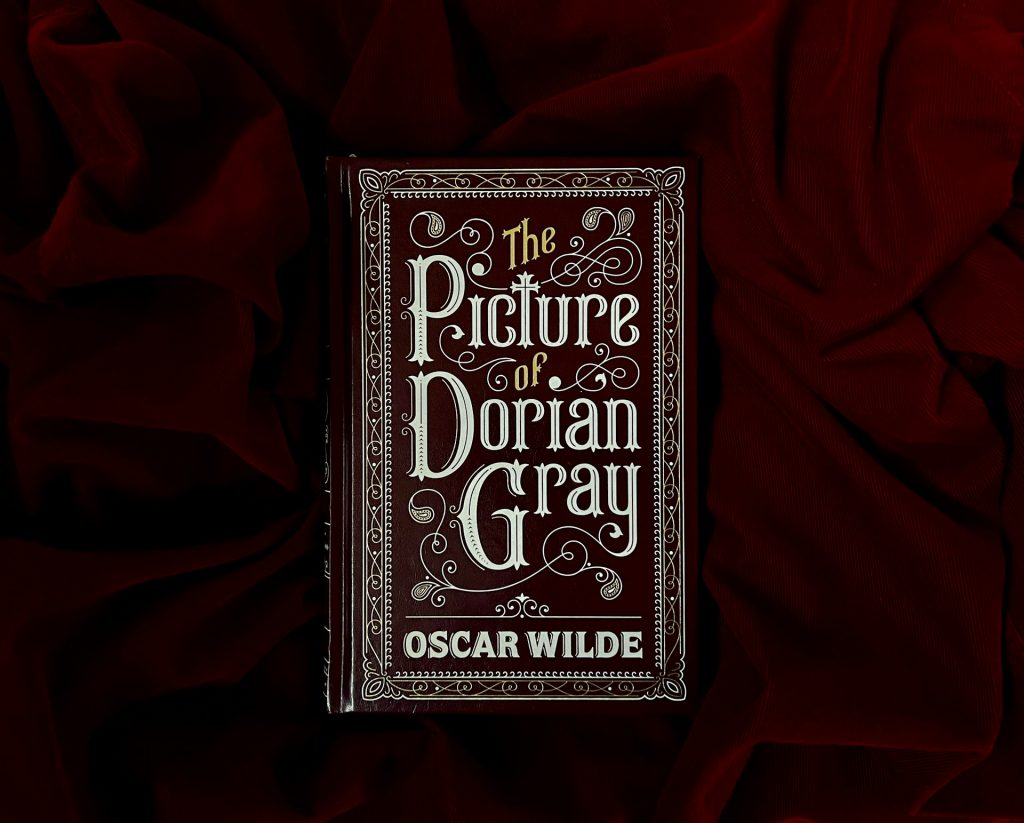

The Picture of Dorian Gray

In this 19th century classic by Oscar Wilde, a supernatural novella with powerful allegorical themes, the central character, Dorian Gray, makes a Faustian bargain: he leads a life of debauchery, sensual excesses and even outright criminality but remains beautiful and young, while his portrait ages. Looking at this handsome young man, nobody is prepared to believe that he is capable of all the things he is suspected of, despite mounting evidence. The Picture of Dorian Gray takes a hard look at youthful desires and forbidden pleasures, and wonders how far one man can go in his perverse attempts to fight aging. But Oscar Wilde refused to accept that this was a morality tale. In his preface he wrote, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written or badly written. That is all.”

In the 20th century, the genre of fiction that engaged most with immortality was science fiction. And in our own century, immortality is increasingly being seen as a matter of when, and not if, by a growing tribe of researchers and futurists. It’s no longer just about story-telling. Yet, as we enter this brave new world, let’s not completely ignore the wise voices from the past who wrote so engagingly about immortality.