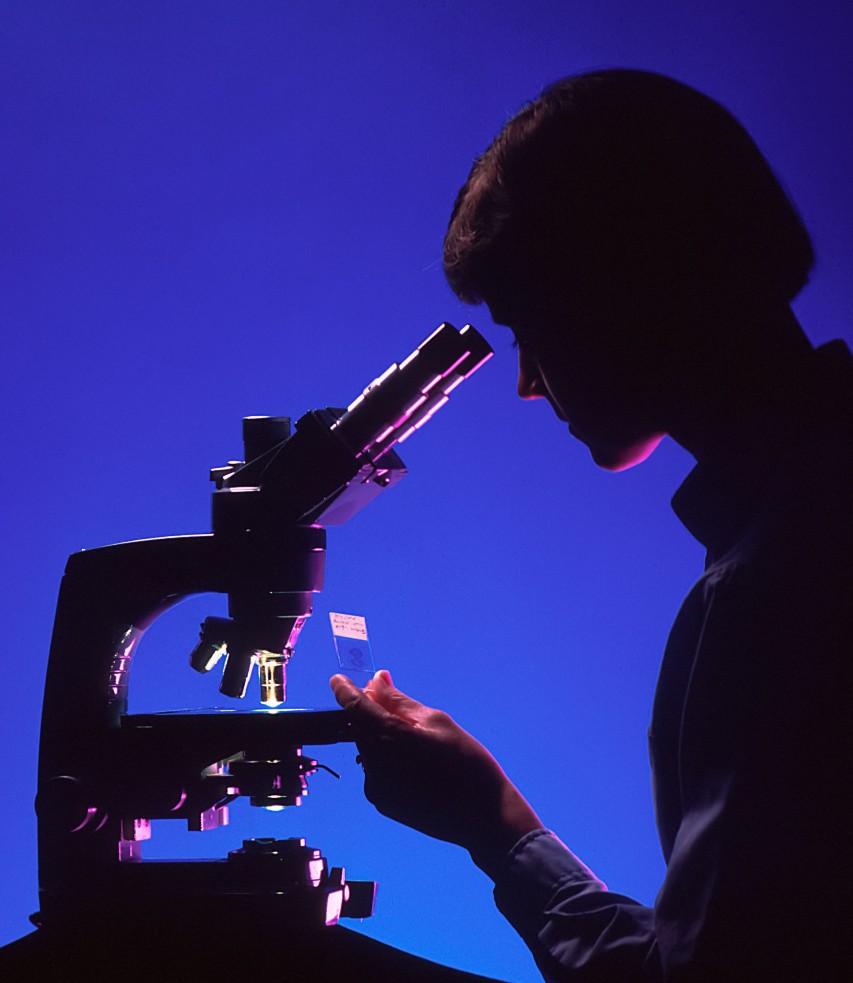

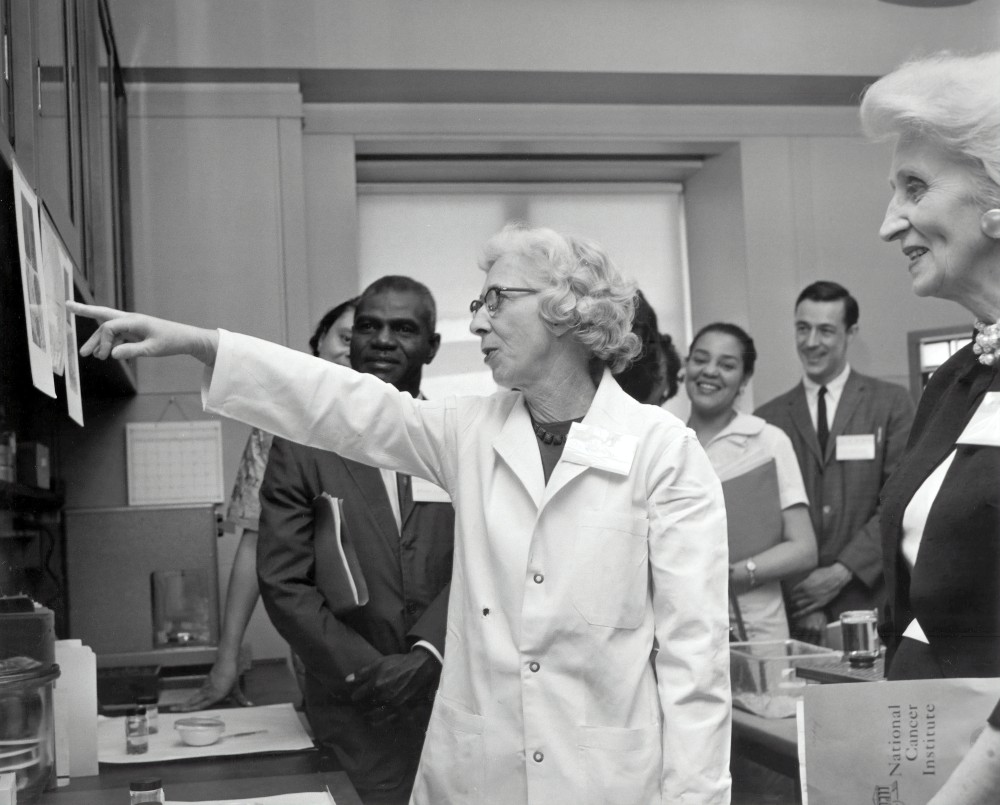

For as long as there have been people in white coats conducting experiments and discovering new technologies, the question of money has never been far away. Materials and laboratories don’t always come cheap, skills can take many expensive years of training to learn, and just like the rest of us, researchers and scientists have rent to pay.

In this respect, cryonics is no different from any other area of human study. It costs money…and there’s no limit to the amount you could spend on research.

But while most academics and researchers around the world have an array of formal grants, funds and subsidies to apply for and (in some cases) squabble over, is this also the case when it comes to cryonics?

The short answer is ‘not really’. But let’s take a closer look at the details — and what they imply for the cryonics community.

‘Mainstream’ headwinds

Before getting into the specifics of — or lack of — formal cryonics funding, it’s important to underline the wider context.

With most ‘mainstream’ government agencies and industry foundations distancing themselves from the concept of cryonics — in the sense of a clinically dead individual being preserved for some future revival — credibility is inevitably a barrier when it comes to funding.

Even though a few influential names, such as the renowned investor Peter Thiel, are believers in cryonics, such voices remain a small minority. Most governments and authorities are simply silent on the subject.

On top of that, when influential organisations in related fields such as cryogenics (the broader study of how materials behave at extremely low temperatures) and cryobiology (similar, but for living things) go out of their way to say they’ve got nothing to do with cryonics, it makes formal funding schemes and investment even harder to justify.

The Society for Cryobiology in the USA, for example, has an explicit position statement stating that: “the act of preserving a body, head or brain after clinical death and storing it indefinitely on the chance that some future generation might restore it to life is an act of speculation or hope, not science…”

In the same text, however, it also states that “conscientious and patient research in cryobiology and medicine” is the only way to achieve what might be considered successful cryopreservation. The sum of these somewhat contradictory messages seems to be that cryonics could in fact be considered a science like any other, but the Society has no intention of getting involved with the “patient research” that would be needed.

The Cryogenic Society of America is also at pains to separate its own work — “the art and science of achieving extremely low temperatures” — from anything to do with cryonics: “We do NOT endorse this belief, and indeed find it untenable,” reads a page on its website.

It is within this context of ‘mainstream’ resistance that the current level of cryonics research funding should be understood.

The Hal Finney Fund

While our hunt for the existence of a dedicated, publicly acknowledged fund for cryonics research has provided little in the way of good news for specialists in the field, one notable exception did emerge.

In 2018, Alcor, the long-established cryonics foundation based in Arizona, created the $5 million Hal Finney Cryonics Research Fund. The donation came from Alcor member Brad Armstrong, who, like Finney, made his wealth in cryptocurrency. The latter, also an Alcor member, has been cryopreserved at the organisation’s Scottsdale facility since losing his battle with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis in 2014.

The fund, which Alcor’s website describes as “unprecedented in the history of the cryonics community”, is broad in its scope. It supports research to:

- Advance the cryopreservation of brain tissue or whole brains, or

- Advance the clinical practice of cryonics, including patient stabilization, transport, and cryopreservation practices.

Beyond this, however, there’s not a lot of information available. It’s not entirely clear whether there is anything ‘left’ in the Hal Finney Cryonics Research Fund, nor whether it is available to researchers without an Alcor connection or partnership, nor how independent researchers could apply for any available funds.

The only additional fact we could establish from the Alcor site is that one of the projects supported by this fund is the Meta-Analysis project.

Timeskipper did attempt to interview someone at Alcor ahead of this article’s publication, but nobody was available for comment.

Formal funding famine

Leaving Alcor behind, there’s little to report in the way of formal funds, subsidies or grants around the world.

Valeriya Udalova, General Director of KrioRus, a russian cryonics service provider, isn’t banking on such backing for cryonics research in her country any time soon:

“Unfortunately, we do not have any financial support from the government or any institution. It’s very difficult to get this kind of support in Russia…ultimately you have to pay for it!”

Peter Tsolakides, founder of the Southern Cryonics startup in Australia, paints a similar picture for cryonics research in his homeland:

“I do not believe there is any cryonics research in Australia and, as such, I am not aware of any funding sources,” he says. “We tend to leverage off what is happening in the US, Europe and perhaps China.”

Which brings us to the Asian superpower. China is home to Yinfeng, a major commercial group active in multiple industries. Since 2016, one corner of its biological subsidiary has been dedicated to cryonics on a non-profit basis — the only organisation in China devoted exclusively to the field.

As is often the case with China, a fundamentally different system makes a direct comparison with the aforementioned countries difficult. Aaron Drake, Director of Research and Chief Specialist at Yinfeng’s Institute for Biological Sciences, explained to us that while there’s a similar absence of formal funds or grants dedicated to cryonics, money does effectively trickle down to cryonics research from the highest levels.

This is partly because this branch of cryonics is part of Yinfeng’s larger organization that makes profit in other areas and is to some degree able to sponsor the division’s life preservation work. But the team is also partnering on research projects with local hospitals and universities — and in China these are inevitably entwined with the government’s financial might.

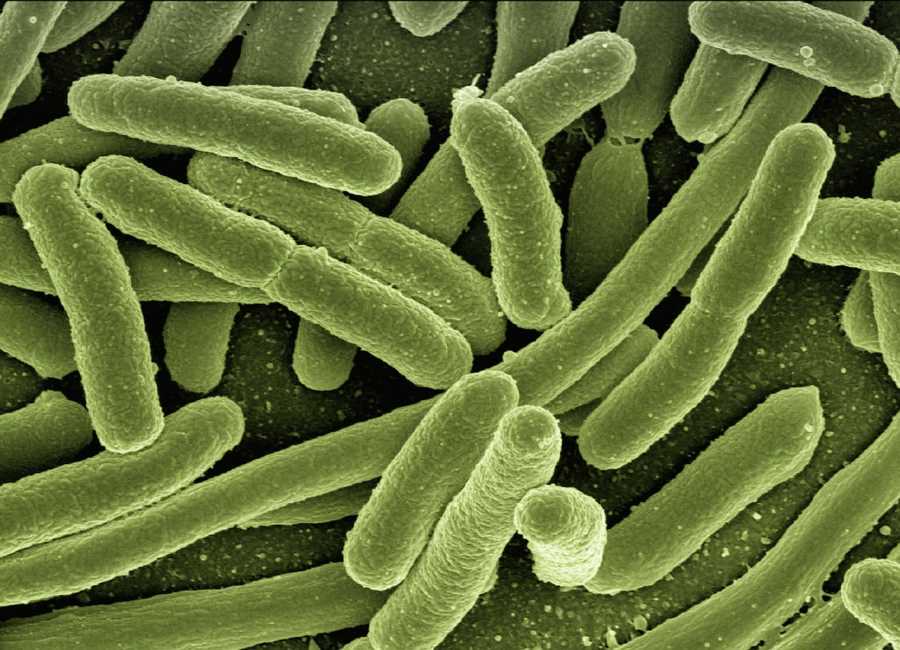

“The Chinese government doesn’t fund whole-body cryopreservation research as such,” says Drake. “But it does have a very strong interest in organ and tissue cryopreservation. And unlike in the west, these two sciences are beginning to intersect in China.”

A do-it-yourself approach

With examples of direct ‘external’ funding for cryonics research around the planet being as rare as they are, it’s little wonder that the cryonics community has learned to take care of its own research needs.

Researchers committed to advancing full-body cryopreservation technology are already used to sourcing their financial backing from private or philanthropic sources. Such sources include, of course, the many paying ‘members’ who have signed up to be cryonically preserved at centers such as KrioRus, Alcor and the Michigan-based Cryonics Institute. Even at Yinfeng, Drake states that the work is primarily “driven by the membership”.

Despite what one might think about this model, it has kept some of these organisations going for decades. Once preservation and running expenses are met, some use remaining funds for their own research projects. Others will make sure it goes to suitable scientists.

Cryonics Institute President Dennis Kowalski says his organisation is strong on the latter front:

“We’ve connected several private donors to Professor Adam Higgins at Oregon University,” he says, going on to suggest that Drake’s ‘intersection’ of cryo-sciences is indeed a trend in the west after all. “While universities don’t freeze whole people, they are responsible for developing new ways to preserve tissues in ways that benefit both cryonics and society at large. Typically, the cryonics community and the cryobiology community have overlapping goals such as best practice in preserving tissues at very cold temperatures.”

While anonymity makes it very difficult to know the extent of private research donations from wealthy individuals, it looks like these remain the best bet for scientists looking for funds, because there’s some evidence that the wider public is far from ready to invest in cryonics research.

Consider Alcor’s attempts to use gofundme to raise cash for its RAPID research project (Readiness and Procedure Innovation/Deployment) — setting up a ‘regular supply’ of cadavres earmarked for medical research. Six months after the 2020 launch of the campaign, the public’s appetite to contribute financially appears to have been muted. At the time of writing, less than 10% of the $70,000 goal has been reached.

And then there’s the Immortalist Society’s effort in 2018 to raise $100,000 for a ‘cryoprize’, which would be awarded to “the first person or group that successfully and verifiably brings a mammalian heart, lung, liver, or pancreas to a cryogenic temperature…and then verifiably restores it to full function according to the rules”.

While this is considered an ‘incentive to research’ rather than research funding per se, and doesn’t go as far as to tackle full-body revival, the subject looks moot as only a little over $3000 has been gathered according to the website. Again, the ‘crowd’ did not seem enthused to make a donation.

Money in the pot

Having worked our way down to the level of ailing crowdfunding schemes, we’re now scraping the bottom of the barrel. There’s a temptation to wonder if the major cryonics organisations are in fact doing exactly the same thing when it comes to research money. After all, the funding environment we’ve outlined means their work is heavily dependent on a small number of wealthy individuals.

Alcor’s blog post dated June 2021 is food for thought. However you want to interpret this request for further cryptocurrency donations, it does demonstrate that the organisation is aware of the need to increase the size of the cryonics research funding pot. As any life sciences researcher will tell you, $5 million only goes so far.

They’d also be likely to agree with the stirring words on the Immortalist Society’s ‘cryoprize’ page which reads: “Scientific research has been the “mother’s milk” of much of the progress of mankind”.

Be that as it may, there appears to be only one way for formal cryonics research funding to go right now. And that’s up!