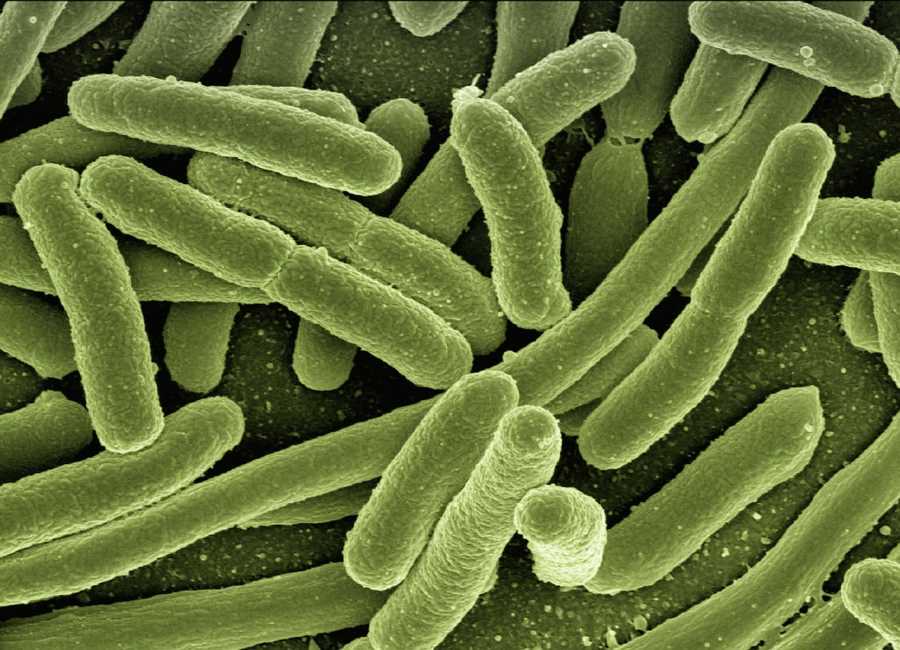

The relationship between humans and microorganisms dates back to the evolutionary origins of ancestral humans, and it is since time immemorial that the human race has exploited the benefits of these microscopic forms of life – may it be for fermenting and brewing, or to use as fertilizers or as tanning agents. With recent advances in microbiological research and biotechnological tools, the importance of microbes has been elucidated even more prominently. There is now ample evidence that they are not just around us, these microbes are a huge part of our very being, of our body and the gut. As the human race strives to live as long as possible, new prospects have arisen regarding the usage of microorganisms and their beneficial biological properties to make a positive impact on human health and lifespan.

The human microbiome

The human body is made up of all sorts of very diverse and numerous species of microbes – bacteria, archaea, virus, protozoa and fungi – referred to collectively as the microbiota. Depending upon the type of interior and exterior environment an individual is exposed to, a distinct profile of microbiota can be found in each individual. Microbes inhabit different parts of the body – gut, skin, mouth, vagina, etc – and they perform several essential functions, impacting the host’s physiology through a symbiotic relationship. On average, an adult human microbiota is composed of 10¹³-10¹4 microorganisms in total that play a crucial role in the break down of food, lipid metabolism and storage, vitamin synthesis, suppression of harmful pathogens, as well as maintaining the integrity of the intestinal barrier. When the normal microbiome is significantly disturbed, dysbiosis occurs, a condition that may lead to various types of pathogenesis including atherosclerosis, cardiovascular disease, depression and anxiety, adiposity and insulin resistance.

In fact, there seems to be a bidirectional causal relationship between the gut microbiome and aging, according to a number of studies that have used various experimental models. In aged individuals, it is argued that one of the effects of age-onset dysbiosis is a decline in immune system function, which coincides with a reduction in the microbiota diversity, causing some specific groups of bacteria to increase in numbers whereas others decrease drastically.

Of particular importance are the bacteria Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli, which promote immune tolerance in the gut, and are found in reduced levels in aged individuals. In contrast, Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridium are the bacteria associated with infection and stimulation of intestinal inflammation whose population significantly rises with aging. Moreover, clinical studies comparing the microbial composition between young and elderly human subjects have shown a reduced microbiota in aged individuals, which has been linked to the development of age-associated type 1 diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis as well as colitis. Such observations are indicative of the fact that the structure of microbiome is directly related to the immunosenescence (aging of the immune system) of the host, and thus research into this field can further any interventions aimed at longevity.

How can we exploit microbes to achieve longevity?

Strategies that involve the modulation of the microbiota are emerging as potential pro-health and longevity interventions that can be exploited. In recent decades, probiotics, one of many promising dietary interventions, has gained serious consideration from researchers, clinicians and nutrition experts. Generally speaking, probiotics are live microbes that have positive health impacts when consumed and/or applied to the body. Generally found in fermented products and dietary supplements, bacterial species like Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium, and yeasts such as Saccharomyces boulardii are but some of the microbes which have a proven track record of enhancing health and consequently the lifespan of model organisms.

Proof of concept: studies revealing a positive correlation between probiotics and longevity

Drosophila (common fruit fly)

In the Drosophila melanogaster, a formulation of synbiotic (probiotics + prebiotics) was found to boost longevity by as much as 60% compared to a conventional diet. In this exciting research published in Nature in 2018, the probiotic strains Lactobacillus plantarum NCIMB 8826 (Lp8826), Lactobacillus fermentum NCIMB 5221 (Lf5221) and Bifidobacteria longum spp. infantis NCIMB 702255 (Bi702255) were found to significantly increase the lifespan of model insects. The authors attributed the role the formulation played in improving longevity to various factors, the chief ones being suppression of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1 via Gut-Brain axis (GBA) communication. IGF-1 is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is generally related to inflammaging-related disorders of the gut, which was significantly suppressed due to the administered formulation as shown by the study.

Mice

In another study that used mice as model organisms, the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium animalis subspecies lactis LKM512 was shown to increase longevity in mice. Its effects were attributed to the suppression of chronic low-grade inflammation in the colon, induced by higher polyamines (PA) levels. Polyamines possess anti-inflammatory activities by inhibiting inflammatory cytokine synthesis in macrophages and by regulating NFkB (an inflammation-related cytokine) activation, hence maintaining the intestinal mucosal barrier function.

Humans

A number of studies in humans, not just in smaller model organisms, have also proven that probiotic consumption enhances the ability to fight infections. In elderly patients, Bifidobacterium lactis HN019 increased phagocytic activity and the population of Natural Killer (NK) cells in elderly individuals. Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 and Lactobacillus acidophilus NSFM in probiotic cheese increased cytotoxicity of NK cells in elderly subjects. Moreover, in another cohort of aged individuals, the probiotic strain in yogurt, Lactobacillus casei DN-1141, was observed to reduce the length of winter infections. In another instance, Pseudomonas and Klebsiella spp found in the human small intestine have been proven to produce significant amounts of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin). This is of particular importance since humans cannot synthesize vitamin B12 and gut microbiota and food are the only sources.

These aforementioned examples are just representatives of why and how microbes can be a useful tool to realise the dream of longevity and increased lifespan. In the future when more research and clinical data is generated, more microbes can be expected to be identified and engineered for this purpose.