The practise of Cryonics, like everything else, has evolved over time. Currently, cryonic-suspension involves the vitrification of legally dead persons in sub-zero temperatures, with the goal of reviving them, should advancements in medicine and technology make headway. The impetus for cryopreservation practices was Robert Ettinger’s “The Prospect of Immortality”. Early cryopreservations were extremely primitive, and disorganised in various aspects. All but one cryopreservation carried out prior to 1974 resulted in failure, either due to insufficient funding or faulty equipment, which eventually lead to the bodies thawing out and being buried or cremated. This article will discuss instances of unsuccessful cryopreservations.

The Preservation of Dr. James Bedford

On 12th January, 1967, Dr. James Bedford became the first person to be cryopreserved. His preservation makes for an interesting study, as he was constantly moved around for a decade and a half before finally being entrusted to the care of Alcor Life Extension Foundation, where he continues to remain in cryonic-suspension.

Immediately after his legal death, the Cryonics Society of California (CSC) carried out his ‘suspension’ in a crude manner. After being injected with a Dimethylsulfoxide solution, Bedford’s body was transferred to a foam-insulated box and covered with one-inch-thick slabs of dry ice. Since this was the first-ever human cryonic suspension, the organization was largely unprepared. Dr. Bedford was moved to the Cryo-Care Equipment Corporation in Phoenix, Arizona six days later. Here, he was stored in a prototype cryo-capsule. This, and the subsequent capsule used, both performed badly, developing leaks in the inner vessel. It was also difficult to determine the liquid-nitrogen levels in the capsules. All these necessitated his transfer to a unit under the care of Glasio Inc.

Amidst all this, the $100,000 set aside by Dr. Bedford to pay for his cryopreservation was more than exhausted in defending the legal battles instituted by his relatives who were against the whole process.

In 1976, when Glasio could no longer house Dr. Bedford, he was moved to the facilities of Trans Time Inc. This move was done using a U-Haul trailer, a sharp contrast to the highly-sophisticated cryonics ambulances currently in use. In 1977, he had to be moved out of the Trans Time’s facility as the cost of storage there was escalating.Therefore, his son took care of his suspension, undergoing multiple inconveniences in terms of procuring liquid nitrogen. Feeling overwhelmed by all the emotional and financial pressure, he was contacted by Alcor in 1982, who offered to continue Dr. Bedford’s suspension in a safer environment and at a lower cost. An agreement was reached and he was finally moved to Alcor’s new facility in Riverside, California in 1987, after being stored at Cryovita laboratories for over four years.

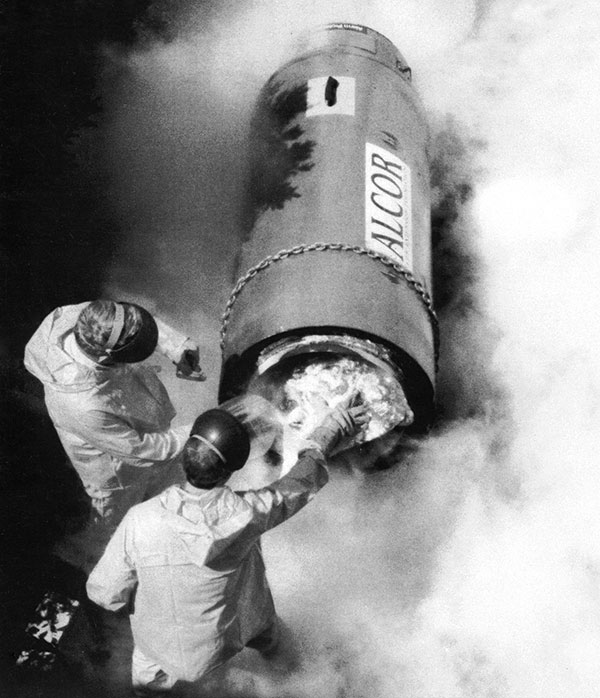

Dr. Bedford being moved into a dewar at Alcor | Source: Alcor

After the death of his wife in 1987, acting on her instructions, Dr. Bedford’s care was irrevocably transferred to Alcor. In 1991, the Glasio unit, in which he continued to be preserved, also failed. Thus he was secured in an aluminium pod and transferred to one of Alcor’s state-of-the-art dewar, after conducting an external examination to evaluate his condition.

Although Dr. James Bedford’s case is not one of a failure, it gives an account of the difficulties that arose due to the unpreparedness of these early organizations, faulty equipment and no proper system to help fund the whole process.

Robert Nelson and the Chatsworth Debacle

After Dr. Bedford, Robert Nelson, the president of the CSC at the time, conducted a series of cryopreservations, all of which failed and thawed out. This was due to a combination of improper funding, unplanned storage and defective procedures.

Marie Phelps-Sweet, Helen Kline and Russ Stanley were all stored in dry ice, at a mortuary, before being unceremoniously squeezed into a Cryo-Care capsule that already contained the body of Louis Nisco. The whole process took a considerable amount of time, which might have caused substantial warming of the bodies. This tightly packed capsule was transferred to an underground vault, owned by Nelson, in Chatsworth cemetery in 1970. Since no fees were collected upfront, the capsule was pretty much abandoned, and the four bodies are believed to have thawed out towards the end of 1971.

Interestingly enough, not having learnt from his past mistakes, Nelson went on to freeze two others, Midlred Harris, in 1970, and Genevieve de la Poterie in 1972. Here too he failed to collect any upfront payments, and the $10,000 donation required would not even cover their cryopreservation. During this period, Steven Mandell, who was initially frozen at CSNY, was transferred to Nelson’s care and these three were stored together in one capsule. A vacuum pump failure disrupted the preservation and the bodies thawed out completely. Although Nelson claimed to have refrozen them, their bodies were no longer viable for reanimation.

Nelson went on to freeze a six-year-old boy, whose identity was not disclosed, in 1974, and Pedro Ledesma in 1976. Ledesma was stored in a mortuary refrigerator for about ten months before being cryogenically frozen, however this lengthy time gap alone would have impaired the suspension. Both the boy and Ledesma were preserved in the same capsule in the Chatsworth crypt and thawed out in 1979.

The media got wind of this story and Nelson was highly criticised. This incident has been infamously dubbed as the “Chatsworth Disaster”. A lawsuit was filed against him by displeased relatives and the Court found Nelson guilty of fraud. Nelson changed his name and went into hiding around 1978.

A Major Case of Capsule Failure

Ann DeBlasio was the third patient that CSNY cryogenically preserved. Eventually, her husband moved her to a cemetery in Butler, New Jersey in 1969, under the care of Nelson. She was frozen in an upright capsule alongside another woman, whose identity remained undisclosed for several years. This capsule, although an improvement over earlier ones, had its own set of drawbacks which proved fatal. In 1978, when the ice over the capsule lid broke, it caused a leak in the vacuum jacket. Although this was fixed and the bodies were safely returned to the capsule, it continued to fail over the next two years which resulted in further meltdowns and decomposition of the bodies. The suspension was terminated in 1980 and the bodies were buried. This was a rare occurrence where, rather than lack of funding, it was the flawed procedure that resulted in cryopreservation failure.

The Wigmaker who ran Cryo-Care

Ed Hope, a wigmaker by profession, was the president of Cryo-Care and his interest in cryopreservation of humans was purely financial. He jumped ship when he found out that it was not going to turn a profit and turned the patients over to their relatives or other organizations. Among these patients was Louis Nisco, frozen in 1967, who ended up at CSC as they offered the lowest rates.

Cryonics Society New York (CSNY)

CSNY was one of the three premier cryonics service providers, alongside Cryo-Care and CSC. The suspension failures associated with CSNY revolve around financial difficulties to maintain those who were cryopreserved. Their first cryonics patient was Steven Mandell, frozen in 1968. He was however moved by his mother to Nelson’s facilities, who offered to maintain him at lower rates, as was the case with Ann Deblasio who, after being stored at CSNY’s facility for some time, was handed over to Robert Nelson for a more economical preservation.

There were also instances where those who initially agreed to fund their relatives’ cryopreservation stopped making the payments, or simply lost interest. This can be illustrated with the case of Andrew Mihok, who had to be buried after only two weeks of being frozen, when relatives refused to pay for his preservation. Paul Hurst, CSNY’s fourth patient, was also thawed when his son no longer wanted to continue making payments. Clara Dostal, another of CSNY’s patients, was preserved for nearly two years before her children could no longer bear the costs and the emotional burden, and were forced to bury her.

Herman Greenberg’s case is a grim example of the inability to fund cryopreservation. Greenberg’s teenage daughter, Beverly, struggled really hard to arrange cryopreservation for her father who died suddenly, by living frugally in order to make ends meet. However, this came to an end after she died from suspected hypothermia in November 1973, while she was sleeping in her truck. Unfortunately, none of their living relatives were interested in making arrangements for their cryopreservation.

Lack of informed consent

An interesting case in which a patient suspended at Alcor’s facility had to be retrieved and buried was that of Sylvia Graham. This was a case where the suspension was arranged by a person other than the patient. Mrs. Graham had not signed any of the documents required for cryopreservation before becoming critically ill. In line with the provisions of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act, her husband, Dr. Marvin Graham, made all the necessary arrangements for her cryonic suspension. About two months later, Sylvia Graham’s sister produced a photocopy of her will in which it was stated that Sylvia wanted a Christian burial, and did not want to be “frozen or cremated”. Litigation ensued on the point of informed consent. The trial court rejected Dr. Graham’s contention that Sylvia had, in fact, decided to sign up for cryopreservation several months prior to her death, and that the process had been delayed due to funding difficulties. Applying the standard of informed consent required for medical experimentation of legally living persons, the Court ruled that Sylvia could not have given informed consent to the procedure, despite any evidence of having changed her mind about cryonic suspension. This, coupled with the existence of her will, was enough to sufficiently override her husband’s authority to make an anatomical donation of her body. In Alcor’s first and only such experience, her body was transported back to her family for burial.

This incident also emphasizes the importance of having all the necessary paperwork in place before conducting a cryopreservation. Currently, all the Cryonics Service Providers strictly require their members to execute all documents and pay the necessary fees prior to beginning any procedure.

Other Instances of Unsuccessful Cryopreservation

The last known suspension failure arising out of lack of funding was that of Samuel Berkowitz, who was frozen and stored in Trans Time’s facility in July 1978. Relatives who were taking care of the funding lost interest in his cryopreservation, and he was buried in 1983.

More recently, in 2006, a French couple, who were frozen for a cumulative period of 24 years, thawed due to a breakdown of the freezer unit in which they were stored; they were stored at a constant temperature of -65C until a technical fault caused the temperature to rise. Their son had no option but to remove the bodies from the freezer and bury them.

Almost all of the cryopreservation failures occurred in the initial years, prior to 1974. The lack of proper funding, along with defective storage techniques and equipment, snowballed into these suspension failures. Another major setback was allowing relatives to fund cryopreservations, as these relatives, more often than not, ended up losing interest. This resulted in the organisations not receiving adequate funding, and ultimately, patients thawing out.

However, as Robert Ettinger said, “There have been some fairly nasty mistakes in the past, of one kind or another, but those appear to be mostly over now, at least the worst.” Nowadays, cryonics service providers have streamlined their funding policies, and ensure that all the requisite paperwork is in place beforehand. The process of cryopreservation has transitioned from freezing to vitrification, and with designated teams to make sure that the preliminary preparations begin immediately after legal death. These improvements show that lessons have been learnt from past experiences.