There is a Latin phrase, taken from a verse in the Bible, which has conditioned art, philosophy and morals far more than any other phrase over the centuries. It is the enigmatic phrase vanitas vanitatum. “Vanity of vanities”, “the infinite vanity of everything”, is a concept that reminds us – as a warning, as a terrible anathema – of the inexorable transience of our reality and, as a corollary, of the fleetingness of our earthly pleasures and daily lives. Art and artists, who have always absorbed the stresses and concerns of the context in which they live in, have in some cases interpreted vanitas literally, while in others, as occurs frequently nowadays, via sublimation and abstraction.

In part 1, we analysed how the fear of death and the desire for immortality were embodied in an idealised manner in ancient Greece, how they turned into a macabre and morbid obsession in the late Middle Ages and were perceived with a human and psychological new approach in the Renaissance era. In this second part, we will move closer to our own era, to see how humanity, through the medium of art, has ratiocinated about its own ephemeral nature, by doing some introspection and self-reflexivity and questioning its own bodily limits and how to overcome them. We will explore how art has introjected the transience and scientific discoveries of the 17th and 18th centuries, the collective trauma and the anguish of the early 20th century, including current performances and installations, which for years have been based on the decadence of the human body, posing new and futuristic dilemmas.

17th century Dutch still-life paintings and the Concept of Vanitas

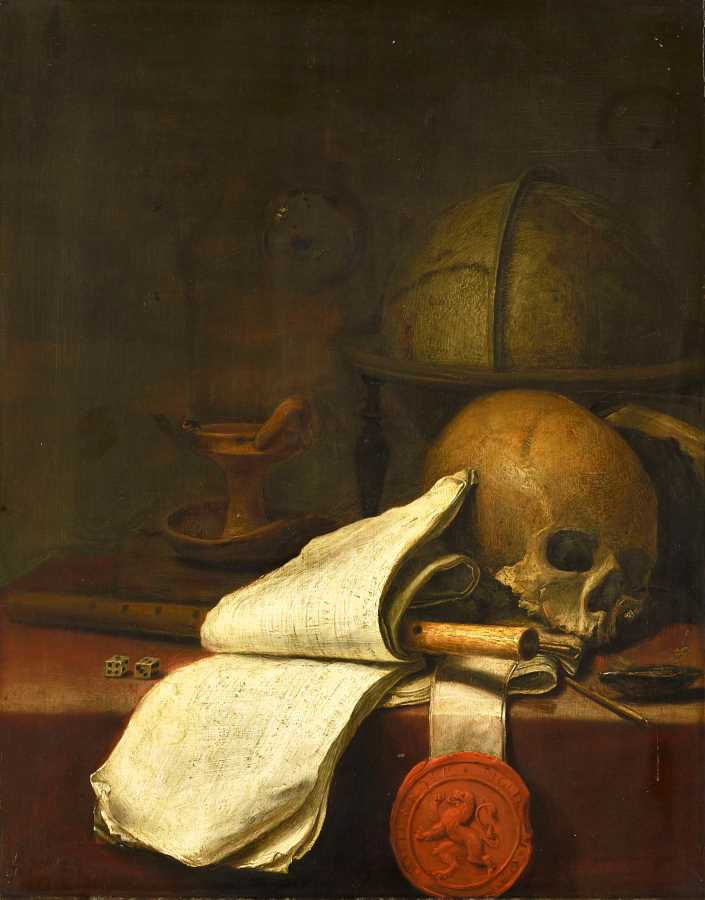

The topics of ephemerality and the immortality of nature have been mostly associated with the art genre of still-life. Some well-known Dutch still-life paintings physically represent the decay of living elements, like rotting fruits and meat or dairy products, literally alluding to the perishing of life; but they also depict jewelry or golden coins, symbols of art and science, like books and musical instruments, and symbols of earthly goods and venal activities, like playing cards, wine glasses, pipes or even skulls. Everything in these paintings became a symbol of the elapse of time, an emblem of vanitas.

This iconography, linked to the precariousness of human condition, was particularly popular in the Netherlands in the 17th century, during a period of wealth, scientific progress and independence, referred to by historians as the Dutch Golden Era. This could seem like a paradox to our modern eyes; therefore why did the Dutch paint skulls and flies at a time of advancement, prosperity, positivity? Well, the Dutch knew that earthly joy as it comes, could also be snatched away. During the Dutch Golden Age, plagues and illness continued to make the population suffer, despite medical advances and new anatomical studies.

Dutch society in the 17th century lived off commerce and was highly consumerist; the objects depicted in these paintings were a celebration of a luxurious and new lifestyle, particularly the more exotic ones. Likewise, being a community of Calvinist faith and therefore with high morals, Dutch artists knew they had to remember the impermanence of these luxuries and joy. Dutch still lifes balanced luxury and indulgence, and juxtaposed prosperity and brevity of life. Their aim was to immortalise, to make eternal, those pleasures, even trivial ones, that are destined to fade away. These paintings can still speak to our Western capitalist society today, so tied to material goods, and immersed in a consumerist and globalised world, just like the one before.

Death and Immortality in 20th century Avant-gardes

The end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century coincided with a political and existential crisis of values. The collapse of religious doctrines and the advent of positivism and a new faith in science were accompanied by a collective sense of crisis and existential anguish. At the end of the 19th century, the collapse of these ideals resulted in art that had reverted back to distressing subjects, often involving death and fear. The theme of immortality was approached with extreme nihilism and the death was often disguised with grotesque appearances.

A true master of the unsettling was the Belgian painter and print-maker James Ensor. His imagery included carnivals, masks, eccentric colours, puppetry…and skeletons. His pastel tones were mistaken for allegories of mortality and a macabre and sombre atmosphere. Death in some paintings is personified and almost mocked by other figures; Ensor confronted the inexorability of this crisis by mocking it.

A very different approach was taken by one of his contemporaries, Edvard Munch, who throughout his life was obsessed with death and the desire to combat the transience of the body and illness. Surprisingly, although the artist’s life was shrouded with grief, he died at almost 80 years old. Death is sometimes literary, sometimes metaphorical. It is solitude, it is terror, but it is a constant presence in his paintings and generally in human life, never ignored.

This dramatic, macabre and suffering character, typical of Ensor and Munch, mainly influenced Expressionism, one of the earliest avant-garde movements. However, the First World War only exacerbated it. The avant-garde artists of the 20th century approached the theme of death in a satirical way, as did the Dadaists, in a revolutionary way like the Futurists, or with an approach dedicated to introspection and psychoanalysis, like the Surrealists. All the avant-gardes were united by the same anguish towards mortality and parallelly by the same destructive charge; their need to overturn the world around them, to kill the past, in order to create a new society and a new, freer, life.

Contemporary perspectives and dilemmas: The right to perish

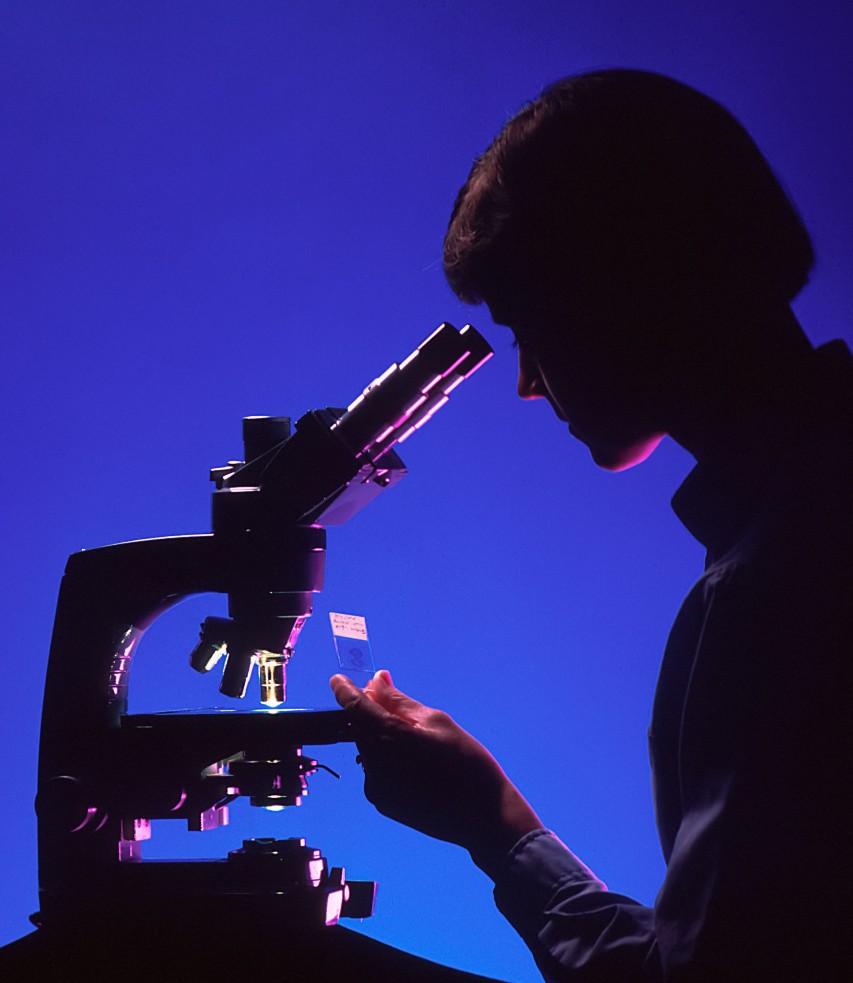

Contemporary Art deals with the topic of immortality and decay of the body from very different perspectives. In contrast to the early 20th century, death is represented by art in a less metaphorical and increasingly biological, scientific, physiological way. All the energies are currently concentrated on removing death from our lives, on the constant thirst for youth, health and immortality.

Nevertheless, art has continued to focus on the ephemeral aspect of life, using perishable materials, like for example the Arte Povera movement, which chose to use natural elements that deteriorate over time in its installations, posing new dilemmas on how to preserve (or not to preserve) works of art. The artist Gino de Dominicis also raised questions about the conception of mortality and immortality by installing a giant skeleton in the middle of Florence. The monumental installation travelled the world, exporting this warning into a universal perspective.

Other even more recent artists have focused on the deterioration of the body and living matter; the most famous artist is undoubtedly Damien Hirst, who literally exhibits animals preserved in formaldehyde. His famous installation, The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, also allows us to reflect on the relationship we have with death – something unreal, frightening, denied – which we cannot fully grasp until we sadly experience it.

In contemporary society, the classical and medieval memento mori has taken on new forms and it has become rooted in a modern perspective, more devoted to life than to the constant, hammering, thought of death. However, in Western culture, death, the greatest repressed element of this century, continues to emerge, especially in times like these, in the midst of a health emergency. The search for immortality, which was once an idealistic and utopist desire, is now closer to becoming a reality, and tangible attempts are being made to prevent death, illness, and the aging process, using all the ultra-technological tools we have at our disposal. We are sure that art will continue to give its interpretation of this complex balance between ephemeral and eternal, life and death, in the future, too.

Aby Warburg (1902): The Art of Portraiture and the Florentine Bourgeoisie.

Zöllner, Frank (2005): “The “Motions of the Mind” in Renaissance Portraits: The Spiritual Dimension of Portraiture”, Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, 68. Bd., H. 1, pp.23-40.

Brown, David Alan (1983): “Leonardo and the Idealized Portrait in Milan”, in Arte Lombarda, Nuova Serie, No. 67 (4), Atti del Convegno: Umanesimo problemi aperti 8, pp.102-116.

Fugelso, Karl (2010): “Music as Im(mortality) in Leonardo’s Portrait of a Man”, in Notes in the History of Art, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp.24-28.