Did the concept of immortality or the fear of death come first? The evolutionary path of human beings has always been accompanied by fears: the fear of disappearing, suffering, and decay, the fear that everything may end, the fear that, after death, there will be nothing. The existential doubt of the afterlife is common to every religion, philosophy, system of belief and cosmogony, in every corner of the world, albeit with very different answers and explanations. And yet, if we hadn’t feared death and hadn’t as a result developed an interest in living as long as possible, are we sure that the idea of immortality and the afterlife would have arisen?

The German philosopher and anthropologist Ludwig Feuerbach argued that mankind does not desire immortality because we believe in it, but we believe because we desire it. From this point of view, there is a very close correlation between the creation of the afterlife in our faith and the desire for immortality, an entirely earthly and human desire, which enables us to banish the unpleasant worm of perishing and illness. According to Feuerbach, we believe in a life after death because we long for it, we hope for it ardently. Theories about immortality and the afterlife have been created to exorcise and master the fear of aging, of decay, of dying and to imagine a future, certainly different, but which in some way retains some similarity with earthly life. Immortality is therefore a concept developed in theology, but also in other spheres, fundamentally because its opposite, mortality, exists.

Humans have always wondered about their worldly existence and what could happen after it. However, the concept of immortality they have developed is quite different from that of eternity. Immortality, as opposed to eternity, refers strictly to a being that has been born, may grow and eventually die but implies that it is a living creature that is destined to continued existence. It is the intrinsic property of living forever, not a timeless realm. This state of survival is often conceived only in the immaterial form of a soul or spirit, after physiological and physical death. But where and how this immaterial existence can continue are still great dilemmas for humanity.

This article will explore the concept of the afterlife, a concept that is common to all religions although it is imagined differently in each of them. In fact, there is a first macro-distinction to be made when talking about beliefs and the afterlife. In some cases, the idea of an afterlife is linked to other worlds, located underground or in the sky, and in any case unreachable. In others, the ‘afterlife’ is viewed as a new, regenerated life, continuing on Earth, or described as specific afterlives, paradisiacal places of pleasure or hell, where human mistakes are punished, as is the belief of the three great monotheistic religions; but we can also see how faith justifies an afterlife still rooted in our Earth, through rebirths and reincarnation, as is often the case in Eastern religions.

People have given themselves answers often guided by common sense, observation of nature or theological, cosmological and philosophical disquisitions. In this age of cultural and religious pluralism the questioning of the afterlife has never been a topic shared by all, even those with a more scientific-rational outlook or who are indifferent to religious issues. There isn’t a religious faith that does not conceive the continuation of life after death in different forms.

Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going? is the title of one of Paul Gauguin’s most famous paintings from the 19th century, an artwork that can be conceived as his testament. This large frieze represents the various ages of life and their respective conditions, but, at the same time, appears to be an Eden, an exotic, primitive, idealized paradise to aspire to. Where are we going? then becomes the existential question, which at least once in our lives, whatever our faith or system of thought, we have asked ourselves.

Paul Gauguin – Where do we come from? Who are we? Where are we going?, 1897 (source: Artble)

The Afterlife in Ancient Cultures and in Classical Antiquity

The idea of immortality and the questioning of the afterlife are ‘ancient doubts’, as old as humanity itself. Human beings of all ages have sought answers, often finding solace in religion, mythology, or metaphysics. One idea, however, that is essential to these answers is that it is always only a part of an individual that survives after physical death, ie. the soul, the spirit, or at any rate a partial element that defines the personality.

This idea is well illustrated by the earliest surviving prehistoric burials, where earthly goods and stone tools were buried alongside the body. Perhaps they were considered useful for the world to come or merely as attributes of their social status in life. This can testify, however, to the fact that mankind believed in life after death in some form, whether it was preparing them for their onward journey into the afterlife or their return to this life.

The recent discovery in the German countryside of a Neolithic skeleton in the fetal position gives new insight into the prehistoric conception of the afterlife: did farmers believe that the death and rebirth of nature were extended to the human body, too? The burial of the deceased in the fetal position, ready to re-born, could reveal a fascinating idea, even primitive, of rebirth connected with the natural cycle.

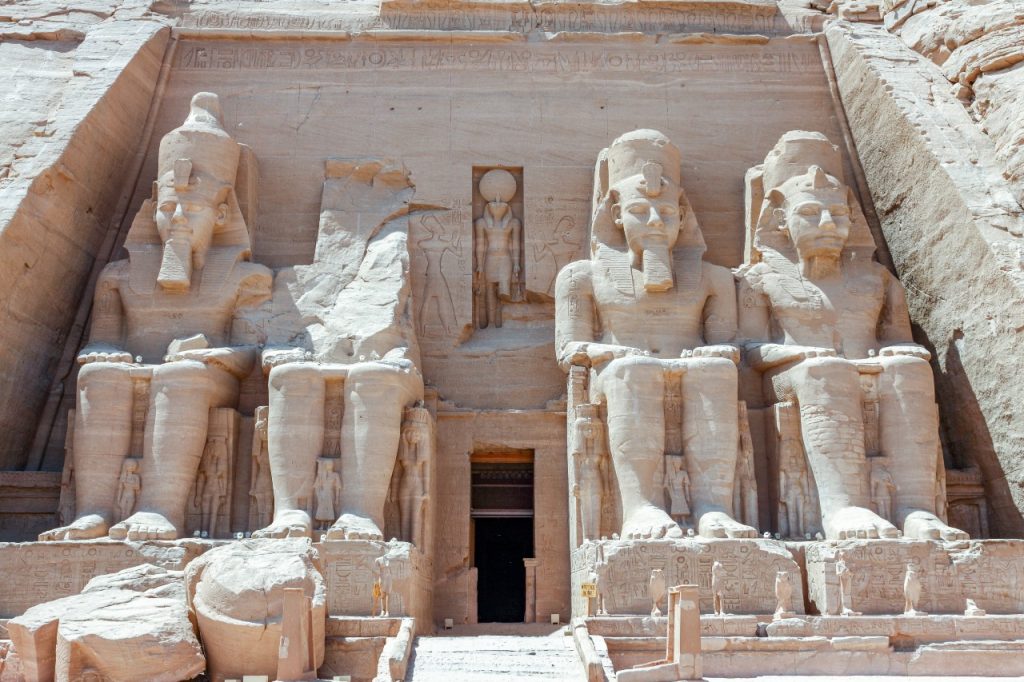

However, it is in Ancient Egypt that the cult of the dead and the formalization of a specific idea about the afterlife begins to take hold. The belief system of ancient Egypt is one of the earliest known in recorded history, and also with regard to the subject of immortality. The cult of Osiris, the god of the underworld, dating back to the 18th century BC, and the funerary practices associated with it, are the earliest evidence of answers concerning the afterlife. The Egyptians believed that man was born with two souls: the Ba and the Ka; the Ba was destined to make the journey to the afterlife, where it was judged on the basis of its actions in life; the Ka, or life-force, was destined to remain with the body and keep it in the tomb, sustained through food and drink offerings. For this reason, ancient Egyptians mummified, placed food, cosmetics, and portraits in the sarcophagi, and embalmed the bodies. Death, after all, was only a temporary suspension as they waited for eternal life. However, the most difficult part of this journey into the afterlife was the ‘Hall of Final Judgment’: the god Anubis would take the deceased to Osiris and his 42 judges, who would weigh their heart against the feather of the goddess Ma’at, a symbol of truth and justice. If the heart was heavier than the feather, it was devoured by the monster Ammut and the soul cast into darkness; if the scales were balanced, the deceased was granted eternal life. A whole life was symbolized by a heart and a feather.

This treatment of the dead in ancient Egypt, however, was initially reserved only for privileged citizens and pharaohs. Only later, with progressive democratization, was it extended to all, extending also the idea of merit: the afterlife is something that must be deserved. The ethical value of this belief, the fear of judgment or sentencing in the afterlife, would later become of great importance in monotheistic religions.

Nevertheless, the description of a real and precise afterlife is to be found in Greek cosmogony, and in classical culture in general, albeit with some dissimilarities to Roman culture. The afterlife in Greek mythology changes according to context but is frequently defined as an underworld called Hades, named after its god and patron. It is described as being located at the edge of the ocean, or in the chasms of the earth, and is a world inhabited exclusively by the dead. Or rather, by the souls of the dead, who once separated from the body after physical death, resume the appearance of their person.

These aimless souls of the dead would have to encounter various crossings before reaching Hades: firstly led by the messenger god Hermes to the entrance to the underworld, ferried over the river Acheron or the river Styx by the boatman Charon (an obolus coin placed on the tongue of the deceased was taken as payment for passage), before passing through the heavy iron gates guarded by the dog Cerberus and appearing before a panel of three judges. Here, too, the dead were judged by Hades himself. Depending on the outcome of the trial, the souls could leave this dark place and enter the Elysian fields or the Isle of the Blessed. These were places described by Homeric sources as spots of peace without conflict, where souls spent a restful afterlife. On the contrary, the wicked would be thrown into the Tartarus, a kind of dark chasm from which there is no escape, where monsters and mortals who were found guilty of terrible misdeeds ended up. This complex cosmogony provides a real contrast between positive and negative afterlife, which is extremely relevant when taking into account the belief of ‘rewarding the good’ and ‘punishing the bad’, typical of some religious conceptions.

Apart from the aforementioned ancient conceptions of the afterlife, there are many others, not as well known but no less fascinating. The Celts, for example, believed in gateways between the real world and Avalon, a mythical island associated with the afterlife, outside the normal bounds of time. According to the Vikings and Norse paganism, only warriors who had distinguished themselves in battle could gain access to the majestic Valhalla and attain immortality; due to this culture strongly based on the value of courage and war, only the “blessed” warriors could continue to fight and enjoy sumptuous meals for eternity. The Native Americans hold no dogmatic conception of the afterlife, and the Christian idea of heaven and hell is alien to their culture; on the contrary, some tribes believe that the souls of the deceased will be welcomed by a village of ancestors.

Depending on what values, priorities, and joys are relevant to a specific culture, the afterlife takes on different forms. They are a mirror of one’s principles and a collective and individual way of mastering death. This reveals an important aspect on a psychological level: it is extremely difficult for human beings to believe in the absence of life in an absolute way. In spite of the different religious, cultural and ethnic explanations, it is practically impossible to conceive of an afterlife, a future existence, which has absolutely nothing to do with the life we actually know.

Ludwig Feuerbach (1981), Thoughts on Death and Immortality From the Papers of a Thinker

Eternity and Immortality (2021) | Exactly, what is Time?|

Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?, Paul Gauguin | Artable|

Karl J. Narr, Prehistoric Religion (2021) | Britannica |

Ashley Cowie, Neolithic Skeleton “Lovingly Buried” in Fetal Position (2020) | Ancient Origins |

Joshua J. Mark, Death in Ancient Egypt (2017) | World History Encyclopedia |

The Editors of Website, The Underworld | GreekMythology.com Website, 08 Apr. 2021

Prof. Geller, Avalon (2017) | Mythology.net|

Joshua J. Mark, Norse Ghosts & the Afterlife | World History Encyclopedia|

Traditional Native Concepts of Death (2014) | nativeamericanroots.net|