“To be, or not to be, that is the question: Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune, Or to take arms against a sea of troubles, And by opposing end them?” – William Shakespeare

In this famous line, Shakespeare, through the character of Prince Hamlet, ponders whether life or death is the better state, or so I was taught at school.

I felt that the lines instead indicated someone struggling with whether they should take what they have been given and accept the terms of life, or enter the fray and live a life that strives for and seeks “more.” A life that does not simply accept terms given but seeks its terms. Active versus Passive.

Many humans have pondered this question. Tomes of philosophy and poetry are devoted to this question. At the end of his life, every poet contemplates whether life has meaning or if all is indeed just vanity. Did my life count for something? But what does this have to do with longevity and space exploration?

Longevity and space exploration

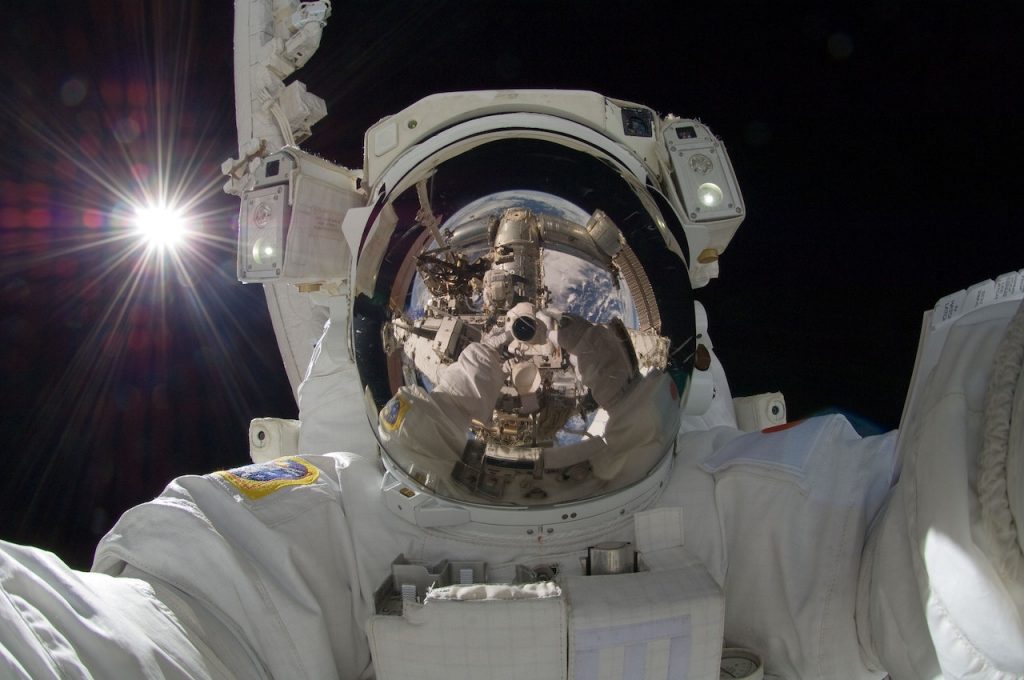

The potential of longevity to unlock space exploration is immense. With longer lifespans, astronauts could travel to distant stars and galaxies as a finite lifespan no longer limits them. In addition, using cryogenics and hibernation would allow astronauts to travel for long periods without aging, revolutionizing space exploration and allowing us to explore farther than ever before, increasing our knowledge of the universe, leading to the discovery of new planets, new life, and civilizations.

In my previous article, I argued that humanity might be one of the first lifeforms to expand into the universe. I based this argument firstly on aspects related to the fermi paradox. Secondly, on the technical and biological difficulty life faces from forming to achieving transformative intelligence, also mentioning how “lucky” humanity has been. And lastly, by considering the universe’s age, not by thinking about its age from beginning to present, but by considering the time from present to end.

Guardian morals and ethics

Now, I would like to take that thought experiment one step further. Let’s assume that we are destined to be the Guardians of the Galaxy and humanity believes we should undertake these two fundamental tasks:

- Humanity believes that we should attempt to manage the universe.

- Humanity believes that it has reached a level of technology that allows us to successfully and positively intervene on behalf of processes, structures, and life forms that cannot protect themselves from forces beyond their control.

Now, if we believe that managing the universe is something we can and should do, what rules should govern our Galactic management strategy? Should we manage the universe the way we handle small ecosystems on earth?

This article will not deal with the technical aspects of universal ecosystems or consider galaxies, galaxy clusters, or solar systems as ecosystems. It will instead deal with one of the primary ethical considerations of intervention, and an exciting spinoff from that.

Saving the dinosaurs

Let us start with a hypothetical question:

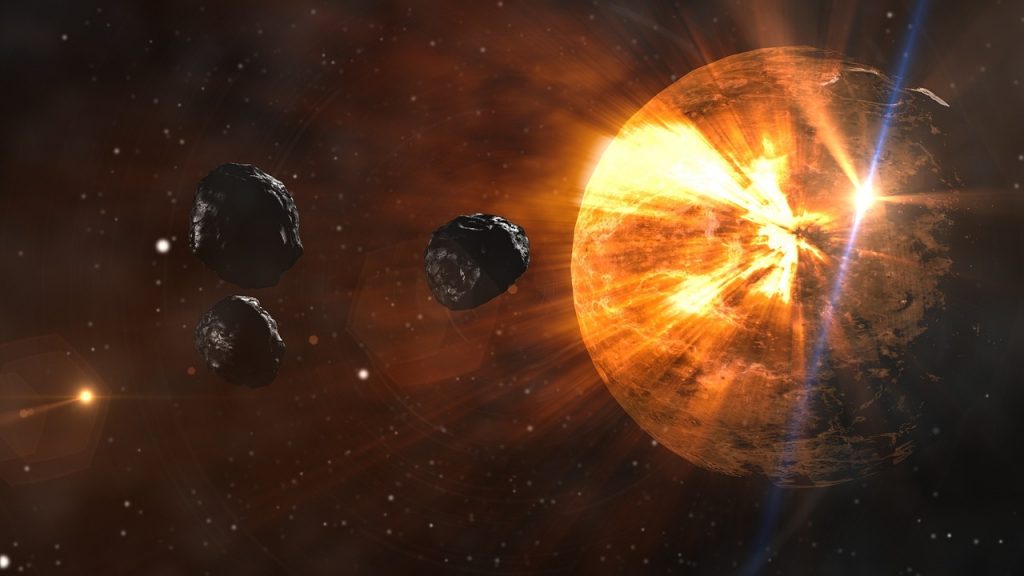

Let’s say that a well-meaning intergalactic alien race visited earth 80 million years ago and fell in love with dinosaurs. Upon discovering that an asteroid was en route and would wipe out the dinosaurs, the well-meaning aliens diverted the danger and saved the dinosaurs.

Then, in a scene approximating a Hollywood blockbuster, after destroying the asteroid, the aliens would high-five each other, or bump limbs per their unique anatomy, heading home and feeling pretty accomplished, blissfully unaware that they had just caused the extinction of thousands of future species, including humans.

It’s straightforward to argue that the aliens did the right thing, but on the other hand, it’s also easy to conclude that they committed a terrible crime. This scenario almost reminds me of the thought experiment that asks whether traveling back in time and killing baby Adolf Hitler would be good, however, you can only know if it’s a good or bad thing once you know the future and have determined that you cannot change it by ensuring young Adolf Hitler gets into art school. The same applies to saving the dinosaurs, in that moment, it could feel right, but what about the future? Can you commit crimes against yet unrealized future species?

Extinction events paving the way

Humanity didn’t rise to the top of the food chain by displacing other species. The universe and its rather unsettling habit of pelting city-sized rocks at planets, in combination with catastrophes caused by climate, took care of most of the heavy lifting needed to get our species to where we are today.

As humans, it’s almost impossible to look at these extinction events rationally and logically without emotion or subjective presuppositions that guide how we “feel” about information and fact.

How should Guardians of the Galaxy act when faced with these dilemmas? The question of whether to be or not to be? Do we intervene to protect the present by maintaining the status quo, and protect the future by preventing change from happening? Or do we leave the universe to evolve, change and adapt, just like it has been doing since its formation? Do we allow the destruction of existing species, a recognized process that allows new species to take the place of those destroyed?

Feelings versus reality

I want to explore this question by contrasting: “how we feel about things” versus “how things really are.”

Let’s take a fever, everyone knows that when a sick child has a fever, you need to give them something for the fever, right?

But what if I told you that fever meds disrupt the body’s natural ability to kill pathogens, thereby increasing the risk of death, and that you are prolonging the suffering? You would think I am a monster suggesting that you allow your child to suffer.

But what if science agreed with me? An article suggesting that we let the fever do its job sounds controversial but is intellectually and scientifically sound.

Our current moment in history dictates that we should act according to what feels right, especially what the majority feels to be correct.

And this brings me to the conclusion that true guardians need to accept suffering as a developmental force that selects, improves, guides, and strengthens.

Is all suffering good?

But what about unnecessary suffering, you ask? I posit that in our civilizational and technological infancy, humanity cannot assert with absolute authority that we know which suffering is necessary and unnecessary. I am not suggesting that all suffering is needed or that we cannot render any judgment on the matter, I am simply stating that our intuition is highly flawed, and that a species that has been around for almost no time at all will make dire mistakes thinking that they can outthink the universe and evolution, which both seem to place a high premium on the value of destruction, calamity, catastrophe, and pain.

Good intentions and unforeseen consequences

Thinking that we “know better” leads to plastic bags replacing paper bags, creating city-sized plastic islands clogging up our oceans. Yellowstone National Park’s ecological management is a case study of how good-intentioned politicians and scientists almost destroyed one of the world’s most beautiful tracts of land.

Current thinking about what is good and what is terrible cherishes happiness and physical joy as the highest good but views anyone who argues to the contrary as evil. Hard lines on the necessity of some suffering, pain, and discomfort are associated with unenlightened thinking. Something primitive and patriarchal. An archaic sense of thinking that doesn’t recognize that the modern world has brought us to a point where suffering is longer needed. But what if suffering is a necessity? Suffering is one of the main drivers of progress for both biological systems and ethics.

I will leave you to ponder this question for yourself. I will also leave you to consider how pain, suffering, and destruction created us and our world. And lastly, I will leave you to wonder whether Guardians of the Galaxy should have saved the dinosaurs, or not.

To be or not to be, that is the question!

Post script: God and suffering

As a Christian, I often face the question of why God permits suffering. When asking the question, I sense that most people are accusing God of being the reason for suffering. A kind of logical flow that goes like this: If you can stop suffering, but you don’t, then you are the cause of it and, therefore, inherently evil.

To some extent, the above article implies that not all suffering is evil. For example, I know that suffering during training makes me stronger and a more effective long-distance runner. In addition, fevers save us from pathogens and help us recover sooner. Everyone who has achieved something great can attest to overcoming physical and mental suffering.

Humanity has a short-sighted view of suffering. We think that it should not exist at all. Would you genuinely like to be unable to mourn the death of your child and feel happy all the time, no matter what?

It is a complex question that sheds light on the utility of all human emotions and physical sensations and how they help us better navigate the complex landscape of life.

So maybe the next time someone asks me why God allows suffering, I will tell them because He is a good Guardian of the Galaxy.